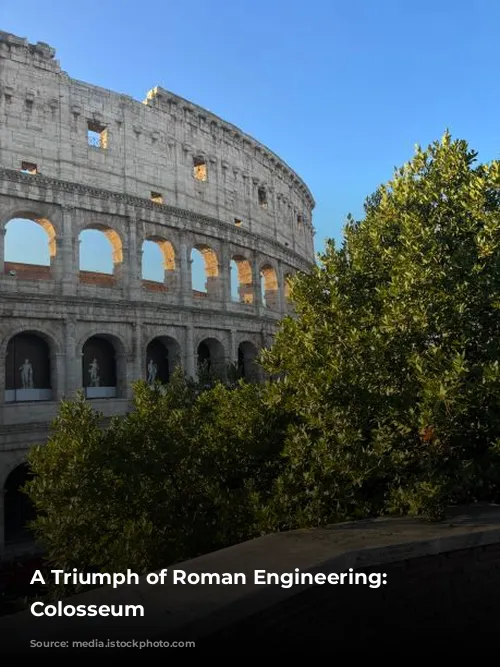

The Colosseum, a magnificent testament to Roman architectural prowess, stands as a colossal reminder of the empire’s grandeur. This iconic amphitheater, the largest of its kind in the world, has endured the ravages of time, surviving fires, earthquakes, and even human neglect. Its imposing presence continues to awe visitors centuries after its construction.

A Symbol of Imperial Power

The Colosseum’s construction began in 70 AD under the reign of the Flavian emperors: Vespasian, Titus, and Domitian. The amphitheater, originally known as the Amphitheatrum Flavium, was a symbol of the Flavian dynasty’s power and a strategic move by Vespasian to appease a populace restless after the tumultuous rule of Nero.

The construction site was a former artificial lake, a remnant of Nero’s opulent Domus Aurea. Thousands of Jewish slaves, captured during the first Jewish-Roman war, provided the labor for this monumental project.

A Colossal Structure

The Colosseum was an oval-shaped structure, measuring a staggering 189 meters in length and 156 meters in width. This massive structure, nearly twice the length of a modern football field, was built from an estimated 100,000 cubic meters of travertine stone – a type of limestone quarried near modern-day Tivoli.

The Colosseum’s construction also involved immense amounts of Roman cement, bricks, and tuff blocks. To bind these massive blocks together, an estimated 300 tonnes of iron clamps were used. The Colosseum’s walls still bear the marks of these clamps, which were scavenged for their metal in later centuries.

A Monument to Roman Might

The Colosseum stood as a powerful symbol of Rome’s might. At the time of its completion, it was the most complex man-made structure in the world. The building’s stark white travertine stone facade soared nearly 50 meters high, an impressive height in an era of predominantly single-story structures. Its massive footprint of 6 acres made it an awe-inspiring sight, comparable to standing at the base of the Empire State Building today.

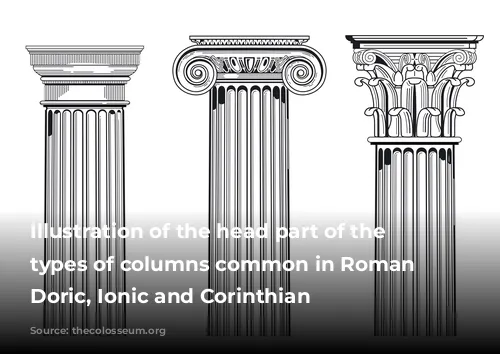

A Symphony of Architectural Styles

The Colosseum exhibited a masterful blend of architectural styles. Each of the three main architectural orders of the time was represented: the austere Tuscan on the ground floor, the slightly more elaborate Ionic on the second floor, and the intricate Corinthian on the third floor. This progression from bottom to top reflected a gradual increase in stylistic complexity.

The building’s exterior was defined by 80 arches spanning the first three floors. Each arch was adorned with a half-column, with the largest arches found on the ground floor. The fourth floor, in contrast, featured flat panels decorated with carvings, azurite, and bronze.

A Stage for Spectacle

The Colosseum boasted two main entrances: the Porta Triumphalis (northwest), used for triumphant processions and gladiator entries, and the Porta Libitinaria (southeast), named after the goddess of funerals, used for removing the bodies of those who perished in the arena.

The Colosseum’s most distinctive feature was its arena, a stage for spectacles of violence and entertainment. The 83-meter-long by 48-meter-wide arena was constructed with a wooden floor covered in sand, sourced from the nearby Monte Mario hill. Trapdoors concealed within the floor allowed for dramatic entrances and exits, creating a sense of wonder and spectacle.

A Social Hierarchy in Stone

The arena was encircled by the cavea, a series of terraces or bleachers, divided into three tiers reflecting the social hierarchy of Roman society. The lowest tier, the podium, was reserved for the most prominent Romans, including senators and high-ranking officials. The gradatio, the middle tier, housed citizens of lesser standing, while the highest tier, the porticus, was occupied by the poorer citizens.

The cavea’s seating capacity was estimated to be around 80,000 spectators. Each seat, crafted from travertine stone, provided ample space for the wealthier attendees who brought cushions for added comfort.

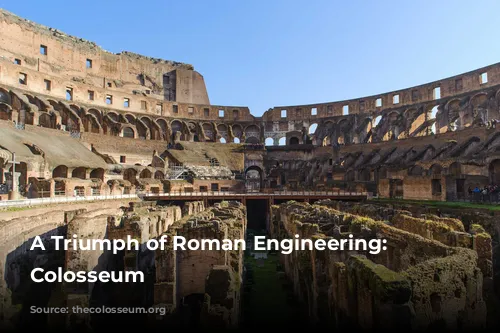

A World Beneath the Arena

While the arena was the Colosseum’s most recognizable feature, its most significant element was the hypogeum, a complex network of tunnels and chambers located beneath the arena.

The hypogeum, added during the reign of Domitian, was a network of tunnels and chambers extending over two levels. It served as a holding area for gladiators and animals before their performances in the arena above. Eighty vertical shafts connected the hypogeum to the arena, allowing for dramatic entrances.

The hypogeum also featured a system of large moving platforms called hegmata, used for raising and lowering large animals, including elephants. A network of underground tunnels connected the hypogeum to the gladiators’ barracks, stables, and even provided a private access tunnel for the Emperor.

The construction of the hypogeum rendered the arena unfit for naumachia, mock naval battles that had been held before its addition. The Colosseum remains a symbol of Roman ingenuity and a testament to the empire’s architectural achievements. Its massive scale, complex design, and enduring legacy continue to inspire awe and wonder in visitors from all over the world.