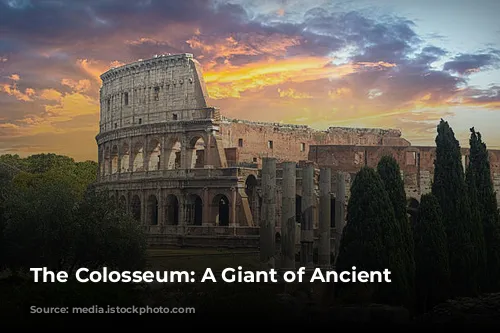

The Colosseum stands as a monument to Roman power and spectacle, the largest and most imposing amphitheatre in the Roman world. Built by Emperor Vespasian of the Flavia family, it was inaugurated by his son Titus in 80 AD.

A Grand Opening

The Colosseum’s inauguration was a lavish celebration lasting 100 days, showcasing breathtaking displays of combat, performances, and hunts. The arena was even flooded to host naumachias, dramatic sea battles recreating famous historical clashes.

Imagine the awe of the spectators as thousands of animals were pitted against each other and gladiators fought for glory and survival. This is a glimpse into the grandeur of the opening ceremonies, a spectacle that captivated the Roman world.

The Colosseum: A Name with History

Why is the Colosseum called the Colosseum? The name originates from a prophecy by the Venerable Bede, a medieval monk, who proclaimed: “Rome will exist as long as the Colosseum does; when the Colosseum falls so will Rome; when Rome falls so will the world.”

He likely got the name from a colossal statue of Emperor Nero, standing near the amphitheatre, which has since been destroyed. The statue, named “the Colossus,” was a testament to the Emperor’s power and ambition.

A Masterpiece of Roman Engineering

The Colosseum, a marvel of Roman architecture, stands as a testament to their engineering brilliance. Originally, the structure was gleaming white, covered in travertine stone slabs. The Colosseum’s elliptical shape maximized spectator capacity, with four floors, each featuring eighty arches.

The second and third floors were adorned with massive statues, adding to the magnificence of the structure. Its imposing scale is a testament to the Romans’ ability to build structures of such grand proportions.

The Colosseum’s Construction: A Feat of Engineering

The Colosseum was built in less than a decade, a remarkable achievement for such a massive structure. The Romans mastered the arch, an ingenious architectural technique that allowed them to distribute weight effectively, making it possible to build such impressive structures.

Think of the Roman aqueducts, another example of their masterful use of arches. The Colosseum can be seen as a series of aqueducts stacked one atop the other, demonstrating the Romans’ remarkable understanding of engineering.

The Colosseum: A Legacy of Time

The Colosseum we see today is a mere skeleton of its former glory. Three-fifths of the outer brick wall is missing, the result of centuries of neglect and plunder. During the Middle Ages, the Colosseum became a quarry for marble, lead, and iron, used to build other famous Roman structures such as Barberini Palace, Piazza Venezia, and even St. Peter’s Basilica.

The holes in the Colosseum’s columns are a testament to this plunder, a reminder of how time has reshaped this once-mighty arena.

A Seat for Every Spectator

The Colosseum could accommodate up to 70,000 spectators, with tiers of seats carefully arranged for optimal viewing. Entry was free for Roman citizens, but seating was stratified based on social status, much like modern theaters.

The top seats were for the common people, with separate sections for men and women. As you moved closer to the arena, you encountered higher social classes, culminating in the front row where senators, vestals, priests, and, of course, the emperor, sat.

Protection from the Sun: The Ingenious Velarium

Just like modern sports stadiums, the Colosseum offered protection from the sun with its ingenious roof covering, the “Velarium.” This massive linen tarpaulin was suspended using ropes, winches, and wooden poles, a system operated by 100 sailors from the Imperial fleet. They moved the Velarium in perfect synchrony, guided by the beat of a drum, creating a spectacle of its own.

The Colosseum’s Arena: A Stage for Spectacle

Stepping into the Colosseum, the arena is the first thing you see. Once covered in a mixture of brick and wood, the arena floor has disappeared, leaving behind the cellars that housed equipment for the games.

Two underground floors housed lifts and hoists with counterweights, remnants of which still exist today. These devices allowed for dramatic entrances of animals and gladiators, who burst into the arena through trapdoors in a cloud of dust, surprising and thrilling the audience.

The Colosseum: A Link Between Citizens and Leaders

The Colosseum’s spectacles were both symbolic and concrete, forging a connection between citizens and their leader. The shows served as a means of public entertainment, providing a distraction from political problems, while also reinforcing the power and authority of the emperor.

Spectacles of the Colosseum: From Animals to Gladiators

The Colosseum hosted a diverse array of shows, each with its own time slot. “Venationes,” or animal hunts, took place in the morning, pitting exotic animals against each other or against human combatants. “Silvae,” meticulously constructed forest scenes, featured animals that were not necessarily killed, showcasing the artistic talents of the time.

The event most enjoyed by the audience was the gladiatorial combats. After a midday break, the arena floor was refreshed with sand, and the roar of the crowd would signify the gladiators’ entry.

The Gladiators: Warriors and Entertainers

Gladiators entered the arena from a passageway connected to their barracks, the Ludus Magnus, where they were trained and prepared. Greeted by their fans like modern-day sports champions, the gladiators would salute the Emperor with the famous words: “Ave Cesare morituri te salutant,” or “Hail Caesar, those who are about to die salute you.”

The term “gladiator” comes from “gladius,” the short sword used by legionaries. While some gladiators were prisoners of war, many chose to fight for glory and freedom. Others were simply seeking a path out of poverty. Gladiatorship offered wealth, fame, and popularity, especially with women.

The Gladiatorial Contests: A Contest of Skill and Will

There were 12 types of gladiators, each with their own unique weapons and fighting styles. The “Retiarius” fought with a net, trident, and knife, while others wielded a shield and sickle, or a javelin and heavy armor.

The gladiators were carefully chosen to create dramatic and exciting matches for the audience. If a gladiator was wounded, he could appeal for mercy by raising an arm. The emperor, seated in his box, would then decide the gladiator’s fate with a gesture: a thumbs-up meant life, a thumbs-down meant death.

The Legacy of Cruelty: A Spectacle of Blood and Violence

Roman spectators relished these spectacles, which we today consider violent and disturbing. Their passion for these events mirrored the modern-day fascination with “splatter” films, but with one key difference: the stark reality of violence.

The smell of blood, burnt flesh, and wild animals permeated the air, a visceral reminder of the brutality of the games. While the Romans attempted to mask the stench with incense and perfumes, the true nature of the Colosseum’s entertainment was undeniable.

The Colosseum: From Arena to Sacred Monument

After the 6th century, as the Roman Empire declined, the Colosseum fell into disuse. Its walls housed confraternities, hospitals, hermits, and even a cemetery.

In the Middle Ages, the Colosseum was declared a sacred monument dedicated to the Passion of Christ by Pope Benedict XIV, symbolizing the suffering of Christian martyrs. A cross was placed on a pedestal, becoming the starting point for the Stations of the Cross on Good Friday.

This designation protected the Colosseum from further destruction, and subsequent Popes initiated restoration and consolidation efforts.

The Colosseum: A Ghost of Ancient Rome

Today, the Colosseum stands as a powerful reminder of the ancient Roman world. For tourists, it evokes, as Charles Dickens wrote, “the ghost of old Rome floating over the places its people walk in.” It is a symbol of the empire’s grandeur, its cruelty, and its enduring legacy.