The Colosseum, a majestic testament to the architectural brilliance and engineering prowess of ancient Rome, stands today as one of the few mostly intact structures from that era. Its enduring presence attracts visitors from around the globe, making it a vital source of tourism revenue for Italy. In 2018, the Colosseum, the Roman Forum, and Palatine Hill collectively brought in over $63.3 million (€53.8 million), surpassing any other tourist attraction in Italy.

This paragraph introduces the Colosseum as a key attraction and highlights its significant contribution to Italian tourism.

From Glory to Decline and Restoration

After the fall of the Western Roman Empire, the Colosseum fell into a state of serious disrepair. During the 12th century, the Frangipane and Annibaldi families repurposed the arena as a fortress, using its massive structure for their own defense. Sadly, in the late 15th century, Pope Alexander VI allowed the Colosseum to be used as a quarry, leading to its further deterioration. This period of neglect lasted for over a thousand years until state-funded restoration efforts commenced in the 1990s.

This paragraph explores the Colosseum’s decline after the fall of the Roman Empire and highlights its transformation from a grand arena to a fortress and, later, a quarry. It then concludes by noting the start of restoration efforts in the 1990s.

A Monument to Entertainment and Imperial Power

The Colosseum was built as a grand project of imperial revitalization, conceived after the tumultuous year known as the “Year of the Four Emperors” in 69 CE. Emperor Vespasian, like other rulers before him, intended the Colosseum to be a vibrant entertainment venue, hosting spectacular gladiator fights, thrilling animal hunts, and even mock naval battles. This arena was a symbol of the Roman Empire’s might, a place where the emperors could showcase their power and entertain the masses.

This paragraph discusses the Colosseum’s original purpose as a place of entertainment, highlighting its importance in the revitalization of Rome under Emperor Vespasian.

From Foundation Stone to Final Touches

Construction of the Colosseum began under Emperor Vespasian between 70 and 72 CE. His son and successor, Emperor Titus, dedicated the completed structure in 80 CE. Emperor Domitian, Vespasian’s other son, added the Colosseum’s fourth story in 82 CE. The arena was funded by the spoils of war – plunder from Titus’s conquest of Jerusalem in 70 CE – and built using enslaved Jews from Judea.

This paragraph provides specific details about the construction of the Colosseum, mentioning its completion under Emperor Titus and the addition of a fourth story under Emperor Domitian. It also highlights the controversial fact that the construction was funded and carried out using Jewish captives from Jerusalem.

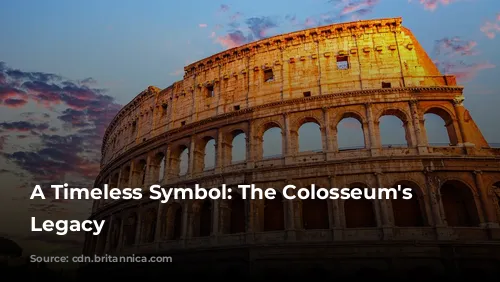

A Grand Amphitheater for a Grand Empire

The Colosseum, also known as the Flavian Amphitheater, is an elliptical structure built in Rome under the Flavian emperors. This architectural masterpiece was constructed using a blend of stone, concrete, and tuff, reaching a height of four stories. Its imposing size – measuring 620 by 513 feet (189 by 156 meters) – allowed it to accommodate an audience of up to 50,000 spectators. The Colosseum was renowned for its gladiatorial combats, where skilled warriors fought for the entertainment of the masses.

This paragraph provides a detailed description of the Colosseum’s architectural features, emphasizing its size and capacity. It also mentions its famous use for gladiatorial combats.

A Symbolic Shift: From Imperial Pleasure to Public Space

The Colosseum’s location just east of the Palatine Hill holds symbolic significance. It was built on the grounds of Nero’s Golden House, where an artificial lake once served as the centerpiece of the emperor’s opulent palace complex. Emperor Vespasian, who rose from humble beginnings to the throne, chose to drain this private lake and build a public amphitheater in its place. This symbolic gesture represented a shift from the tyrannical emperor Nero’s personal pleasure to a public space for the entertainment and unity of the Roman people.

This paragraph delves into the historical context of the Colosseum’s location, emphasizing its symbolism as a replacement for Nero’s private lake. It highlights Emperor Vespasian’s intention to create a space for the public, symbolizing a shift from imperial excess to public enjoyment.

A Masterpiece of Engineering and Design

The Colosseum stands out from earlier amphitheaters due to its innovative design and engineering. Unlike earlier structures, which were often built into hillsides for extra support, the Colosseum is a freestanding marvel of stone and concrete. Its intricate system of barrel vaults and groin vaults allowed it to reach its impressive size. Three of its stories are adorned with arcades framed by engaged columns in the Doric, Ionic, and Corinthian orders, creating a visually stunning architectural assemblage. The Colosseum’s facade is made of travertine, while the interior walls are constructed of volcanic tufa and concrete.

This paragraph focuses on the Colosseum’s innovative design and construction techniques. It contrasts it with earlier amphitheaters and highlights its use of stone, concrete, and a complex vault system.

Ensuring Comfort and Protection for the Crowd

The Colosseum’s design prioritized the comfort and safety of its massive audience. Up to 50,000 spectators could enjoy the spectacles, shielded from the sun by a massive retractable awning known as a velarium. Supporting masts extended from the top story, and skilled Roman sailors manipulated the rigging to extend and retract this awning, providing shade for the crowds. The Colosseum became the stage for countless gladiatorial contests, battles between men and animals, and even mock naval engagements. However, the authenticity of the popular belief that early Christians were martyred in the arena remains uncertain.

This paragraph describes the Colosseum’s features that ensured the comfort and safety of its spectators, emphasizing the retractable awning that protected them from the sun. It also lists the various spectacles held in the Colosseum, while acknowledging the uncertainty about the supposed martyrdom of early Christians.

From Glory to Ruin and Back: A Monument Restored

The Colosseum’s glory faded during the Middle Ages, when it was repurposed as a church, then as a fortress by prominent Roman families. The arena suffered damage from lightning, earthquakes, and, most significantly, vandalism and pollution. Precious marble seats and decorative materials disappeared, as the Colosseum was treated as a mere quarry for over a thousand years. Preservation efforts began in earnest in the 19th century, with notable contributions by Pope Pius VIII. A major restoration project was undertaken in the 1990s, reviving this ancient monument. The Colosseum now stands as one of Rome’s most visited tourist attractions, welcoming close to seven million visitors annually. Regularly mounted exhibitions explore the rich culture of ancient Rome, ensuring that the Colosseum continues to inspire awe and wonder in its visitors.

This paragraph recounts the Colosseum’s decline and restoration, emphasizing its transformation from a quarry back to a major tourist attraction. It highlights the ongoing efforts to preserve the monument and the regular exhibitions showcasing ancient Roman culture.

A Symbol of Ancient Rome’s Enduring Power

The Colosseum remains a powerful symbol of ancient Rome’s architectural and engineering prowess. It stands as a testament to the ingenuity and skill of the Romans, captivating generations of visitors with its awe-inspiring grandeur. Its enduring popularity as a tourist destination ensures that its legacy will continue to inspire and enthrall for centuries to come.

This concluding paragraph reiterates the Colosseum’s significance as a symbol of ancient Rome’s architectural and engineering achievements and emphasizes its enduring appeal as a tourist attraction. It leaves the reader with a lasting impression of the Colosseum’s importance and impact.