Christianity’s early years were modest, attracting minimal attention from both pagans and Jews. Yet, its growth during the Roman era marked a significant shift in the religious landscape. Scholars now recognize early Christianity as a pivotal movement within Judaism, mirroring its apocalyptic and eschatological beliefs. Jesus himself is now seen as an apocalyptic prophet, whose teachings aimed to fulfill rather than abolish the Torah.

Jewish Roots and Christian Expansion

Christianity’s roots extend deeply into Jewish traditions, both in Palestine and the diaspora. This is evident in shared practices like martyrdom, proselytism, monasticism, mysticism, liturgy, and theology. The concept of the Logos, or Word, serving as the bridge between God and the world, resonates with both Jewish and Christian thought. The Septuagint, a Greek translation of the Hebrew Bible, played a crucial role in shaping the early Church’s theological interpretations.

Christianity’s embrace of Hellenism set it apart from Pharisaic Judaism, particularly under the leadership of the Hellenized Jew Paul. Though Paul opposed Torah observance as the path to salvation, many Jewish Christians continued to practice it. Notably, two groups emerged: the Ebionites accepted Jesus as the Messiah but rejected his divinity, while the Nazarenes recognized both his messiahship and divinity but adhered to the Torah.

The number of Jews converting to Christianity remained minimal, a fact reflected in Christian writings criticizing Jewish stubbornness. Despite the strong influence of Hellenism, Jewish conversions were scarce outside of Alexandria, where Christianity found some success.

The Final Break: A Series of Events

The separation of Christianity from Judaism was marked by a series of pivotal events:

- The flight of Jewish Christians to Pella, across the Jordan in 70 CE, during the Roman destruction of Jerusalem, symbolized a growing divide. Their refusal to join the fight against the Romans further deepened the chasm.

- The inclusion of a prayer against heretics in the Eighteen Benedictions by the patriarch Gamaliel II around 100 CE marked a formal break by Jewish authorities.

- The failure of Christians to participate in the messianic rebellions led by Lukuas-Andreas and Bar Kokhba in 115–117 and 132–135 CE, respectively, further solidified the separation.

The Jewish Response: From Revolt to Renewal

Roman rule over Judea began in 63 BCE when Pompey intervened in a civil war. This was followed by a period of Jewish autonomy under Herod the Great, an Idumaean king who embraced Greek culture. After Herod’s death, the region was ruled by Roman procurators, culminating in the notorious Pontius Pilate, who attempted to install Roman emperor busts in Jerusalem, sparking intense Jewish resistance.

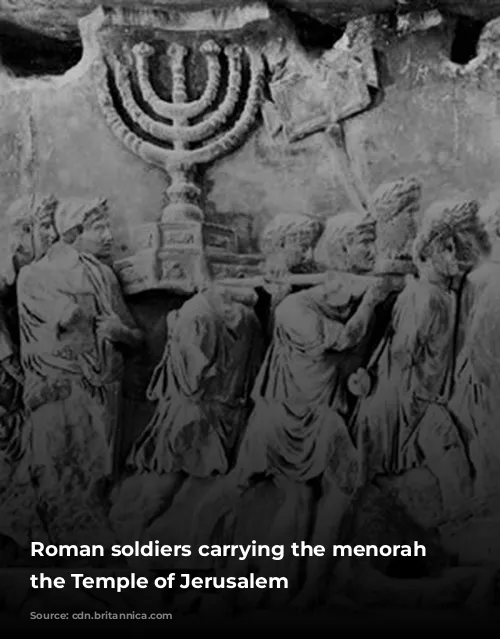

The Jewish desire for freedom from Roman rule led to multiple rebellions. The first war with Rome in 66 CE ended in the destruction of the Temple in 70 CE. This was followed by widespread uprisings involving Jews from Egypt, Cyrenaica, Cyprus, and Mesopotamia, culminating in the Second Jewish Revolt led by Bar Kokhba in 132–135 CE. These rebellions resulted in harsh Roman reprisals, including bans on circumcision and Torah instruction.

Despite suffering immense losses, Judaism found strength in its resilience. This period of intense persecution led to a renewed focus on the development of the Talmud, a monumental work of Jewish law and tradition.

The separation of Christianity from Judaism was a gradual process, driven by religious, political, and cultural factors. While both faiths share deep historical and theological roots, they ultimately diverged, each pursuing its own distinct path. The story of their separation is a testament to the complex interplay of faith, tradition, and history.