Imagine a world where thousands of animals were slaughtered for entertainment. This was the brutal reality of ancient Rome, where “venationes” – staged hunts – captivated audiences with their bloody spectacle.

This article delves into the gruesome history of venationes, exploring the origins, the types of animals involved, and the lasting impact on the environment.

The Beginning of a Bloody Tradition

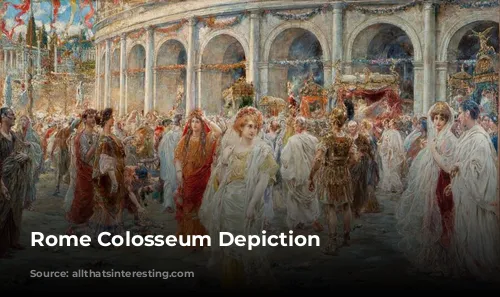

The Romans, known for their elaborate spectacles, were always seeking new thrills. Chariot races and gladiator combat were already popular, but the desire for more blood-pumping entertainment led to the rise of venationes.

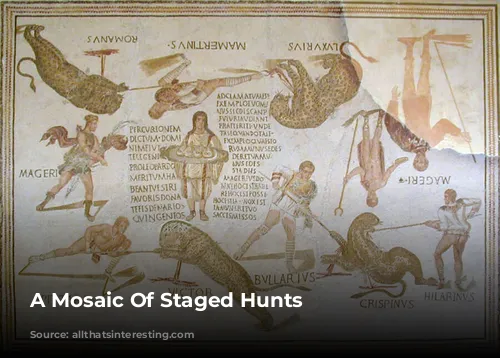

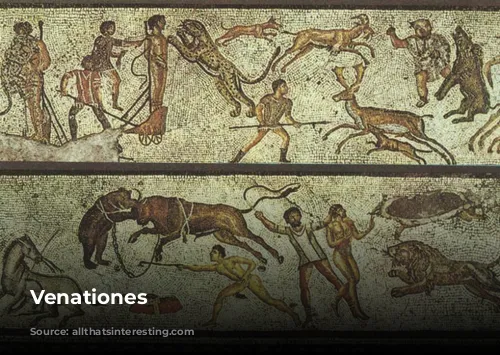

These staged hunts, featuring exotic animals, were a sight to behold. Lions, bears, elephants, and other beasts, brought from across the Roman Empire, were pitted against each other, or against specially trained warriors called “venatores.”

While some estimates place the beginning of venationes as early as 252 B.C., with Pliny the Elder documenting elephants captured during the First Punic War, the first documented venatio took place in 185 B.C., after the Second Punic War.

Roman general Marcus Fulvius Nobilior, celebrating his victories in Greece, staged a hunt featuring lions and panthers. Livy, the Roman historian, described this event as a new kind of athletic spectacle, showcasing the “resources and variety that the entire age could muster.”

The era of venationes was officially underway, ushering in an age of bloodshed and spectacle.

The Animals of the Arena

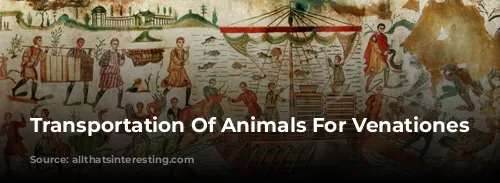

The Roman Empire stretched across vast territories, allowing them to collect exotic animals from all corners of the known world. North African lions, Scottish bears, Persian tigers, Indian crocodiles, and rhinos were all brought to Rome to participate in these brutal spectacles.

Capturing these animals was a dangerous and challenging task. Hunters used dogs, trumpets, nets, and pits to subdue these formidable creatures. Oppian, a poet, vividly described the danger of capturing bears, stating that they would “rage with jaws and terrible paws” when cornered.

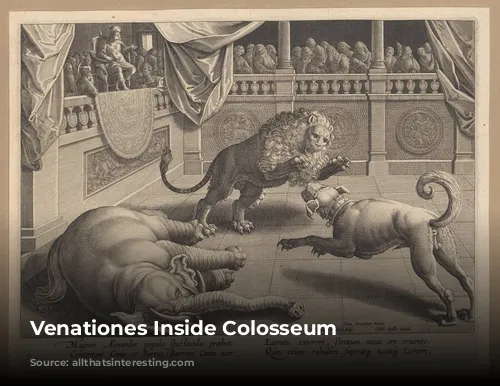

Once in Rome, these animals were often forced to fight each other, or against venatores.

The Men Who Faced the Beasts

The venatores, much like gladiators, were often slaves, criminals, or individuals contracted to fight. They were considered even lower in social standing than gladiators, despite undergoing rigorous training in fighting schools.

Initially, animals were chained to make the venatores’ task easier, but by 100 B.C., animals were allowed to roam freely. This necessitated the construction of high walls in the Colosseum to prevent animals from escaping into the audience.

Venationes were held for various reasons: honoring deities, celebrating victories, or marking monumental occasions like weddings, funerals, or the coronation of emperors.

The Emperors’ Obsession with Blood

The Roman emperors were particularly enthusiastic about venationes. Emperor Titus, upon inaugurating the Colosseum in 80 A.D., hosted a 100-day spectacle that saw over 9,000 animals slaughtered.

Emperor Trajan, eager to surpass Titus, held a venatio in honor of Rome’s victory over the Dacians. Lasting more than 120 days, it resulted in the death of 11,000 animals – an average of over 90 animals per day.

Some emperors, like Commodus, even participated in the hunts themselves, seeking inventive ways to kill animals. Commodus, a self-proclaimed gladiator and venatore, invented a crescent-shaped arrow to kill ostriches. The sight of headless ostriches running around in the arena captivated the Roman crowds.

Other emperors, like Septimus Severus and Probus, went even further, creating elaborate set pieces like ships that broke apart to release animals or turning the arena into a mock forest. These emperors competed to outdo their predecessors, ensuring the spectacle of venationes continued to amaze and horrify the Roman populace.

The Decline of the Bloodlust

By the 3rd and 4th centuries, the popularity of venationes began to wane. The declining availability of exotic animals due to Roman expansion and financial constraints played a role.

The rise of the Christian church and changing social values also contributed to the decline. In 404 A.D., a monk named Telemachus intervened in a gladiatorial match, attempting to stop the violence. He was killed, and the emperor Honorius subsequently banned gladiatorial combat.

Venationes continued for a while, but the insatiable bloodlust of earlier centuries had waned. Romans no longer had the appetite or budget for the mass slaughter of animals.

A Legacy of Bloodshed

While venationes ended in the 7th century, their legacy lives on. The Roman obsession with exotic animals, fueled by their desire for spectacle, resulted in the extinction or near-extinction of many species, including the European wild horse, the Eurasian lynx, and the North African elephant.

Rome’s vast territorial expansion coupled with destructive farming practices turned fertile land into barren deserts, leaving a lasting mark on the environment.

Today, the idea of venationes seems unimaginable. Yet, our fascination with exotic animals persists, reflected in our visits to zoos and aquariums. While these modern-day attractions aim to educate and entertain, they also highlight our ongoing connection with the natural world, even as we strive to learn from the mistakes of the past.