The Colosseum, a testament to Roman architectural brilliance, stands as the world’s largest amphitheater. Despite enduring countless fires, earthquakes, and the ravages of time, this awe-inspiring structure continues to captivate the imagination. Its journey, however, began centuries ago during the reign of the Flavian Emperors.

From Flavian Dreams to Public Favor

The Colosseum was a grand undertaking, constructed between 70 AD and 80 AD under Emperors Vespasian, Titus, and Domitian. Originally called the Amphitheatrum Flavium, it was a symbol of the Flavian dynasty’s ambition. Vespasian, in particular, saw the Colosseum as a way to win back the favor of a restless populace after the turbulent reign of Nero. Construction commenced in 72 AD on the site of Nero’s lavish Domus Aurea, a reminder of the emperor’s excesses.

Building a Monument to Power: Labor and Materials

The Colosseum’s construction involved a massive labor force, primarily Jewish slaves captured during the first Jewish-Roman war. This monumental task required an immense amount of materials. An estimated 100,000 cubic meters of travertine stone, a type of limestone mined near Tivoli, formed the foundation of the building. This was supplemented by Roman cement, bricks, and tuff blocks. To bind these colossal blocks together, an astounding 300 tonnes of iron clamps were used, sadly scavenged in later centuries, leaving telltale pockmarks on the Colosseum’s walls.

A Marvel of Architecture: From Stone to Splendor

The Colosseum was a breathtaking spectacle. Its towering height of nearly 50 meters and its expansive footprint of 6 acres made it a dominant presence on the Roman skyline. Constructed primarily from white travertine stone, it would have shimmered in the sun, a symbol of Rome’s power and grandeur. Imagine standing at the foot of the Empire State Building today; the Colosseum would have had a similar impact on an ancient Roman.

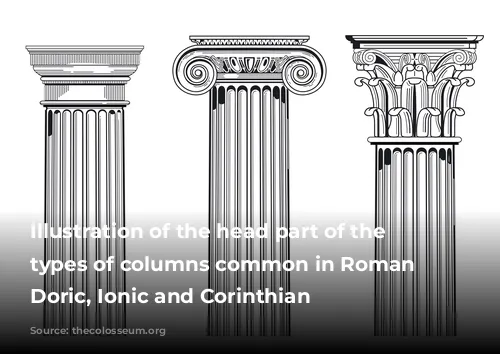

A Blend of Architectural Styles: Tuscan, Ionic, and Corinthian

The Colosseum showcased the mastery of Roman architecture, incorporating all three major architectural orders of its time. The ground floor boasted Tuscan columns, a Roman variation of the austere Greek Doric style. The second floor featured slightly more elaborate Ionic columns, while the third floor embraced the intricate and decorated Corinthian style. This progression from bottom to top created a visual hierarchy of stylistic complexity. Each half-column served as the centerpiece of an arch, with 80 arches forming the building’s perimeter on the first three floors. These arches, largest on the ground floor, gradually decreased in height as they ascended.

Beyond Arches and Columns: The Fourth Floor and the Entrances

The fourth floor, however, deviated from the arch-and-column motif, opting for flat panels instead. These panels, thanks to recent cleaning efforts, have revealed intricate carvings and insets of azurite and bronze. The Colosseum had two main entrances: the northwestern Porta Triumphalis, through which gladiators entered the arena, and the southeastern Porta Libitinaria, named after the goddess of funerals, Libitina, used to remove the bodies of those who perished.

The Arena: Where Battles and Spectacles Unfolded

The Colosseum’s most striking feature, the arena, was a rectangular space measuring 83 meters in length and 48 meters in width. Its wooden floor, covered with sand from the nearby Monte Mario hill, held the stage for gladiatorial contests, animal hunts, and other spectacles. Trap doors concealed within the floor allowed for surprise entrances and exits, creating dramatic effects. A 10-foot wall surrounded the arena, leading to the first level of seats.

A Social Hierarchy in Stone: The Cavea

The cavea, the tiered seating surrounding the arena, reflected the social hierarchy of Roman society. Divided into three levels—the podium, gradatio, and the porticus—it offered a glimpse into the social stratification of Roman life. The podium, closest to the arena, was reserved for the elite, including senators and high-ranking officials. As one ascended the cavea, the social standing of the spectators decreased, with the top tier occupied by Roman citizens, albeit those of lower status. Each seat, crafted from travertine stone, was approximately 40 centimeters wide, and wealthier attendees brought cushions for comfort. The Colosseum could accommodate an estimated 80,000 spectators.

Navigating the Cavea: Scalaria and Vomitoria

The cavea was accessed through scalaria, stairs leading to the stands, and vomitoria, passages leading to the exterior. Contrary to popular belief, vomitoria were not for vomiting; the name refers to their function of “spewing forth” people.

The Hidden Heart: The Hypogeum

While the arena was the Colosseum’s most striking feature, the hypogeum, its underground area, was its most important. This network of tunnels and chambers on two levels housed gladiators and animals before their performances in the arena above. Added after the Colosseum’s inauguration in 80 AD by Emperor Domitian, it was connected to the arena by 80 vertical shafts, allowing gladiators and animals to access the arena floor. The hypogeum also incorporated large moving platforms called hegmata, used to transport large beasts such as elephants.

A City Beneath the Arena: Tunnels and a Private Entrance

A network of underground tunnels connected the hypogeum to the gladiators’ barracks and nearby stables. The Colosseum even boasted a private access tunnel for the Emperor, allowing him to enter and exit the building safely, avoiding the crowds. The construction of the hypogeum, however, rendered the arena unfit for naumachia, mock naval battles. Only two were held before the hypogeum’s construction.

Conclusion: A Legacy of Wonder and Power

The Colosseum stands as a testament to the architectural and engineering prowess of the Roman Empire. Its sheer size, intricate design, and historical significance continue to captivate the world. From its grandeur to its hidden secrets, the Colosseum is a window into the past, offering a glimpse into the lives, customs, and aspirations of a long-gone civilization.