The Colosseum, a symbol of Roman grandeur, stands as a testament to the ingenuity and architectural prowess of the ancient world. This iconic amphitheater, built in the 1st century AD, has captivated the imagination of millions for centuries. But beyond its imposing exterior lies a world of secrets waiting to be unearthed. Let’s embark on a journey through the Colosseum’s intricate design, exploring its structure, its arena, its seating arrangements, and the fascinating world beneath its surface.

A Masterpiece of Roman Engineering

The Colosseum’s structure, a marvel of Roman engineering, is a harmonious blend of different materials. The outer walls and load-bearing pillars are made of sturdy travertine blocks, while the radial walls and stairs are crafted from bricks and tufa blocks. This combination of materials provided strength and stability, enabling the amphitheater to withstand the test of time.

Rising to a height of about 50 meters, the building’s exterior is divided into four levels. The topmost level was adorned with a marble colonnade, remnants of which are still visible today. The Colosseum’s elliptical shape is undeniable, with a long axis of 188 meters and a short one of 156 meters.

Stepping into the Arena: Witnessing History in Action

Walking into the Colosseum, one can’t help but feel a sense of awe. The arena, the heart of the amphitheater, was originally covered with sand – hence the Latin term arena. Today, the arena floor is gone, but remnants of its foundation remain.

The amphitheater boasted 80 archways, each serving a specific purpose. 76 of these entrances were numbered, guiding spectators to their designated seats. The remaining four, strategically placed at the ends of the ellipse’s axes, were reserved for the emperor, political and religious authorities, and the stars of the spectacle. The monumental entrances on the short axis led to two royal boxes near the arena, one of which was reserved for the emperor.

A Seat for Everyone: Social Hierarchy in the Colosseum

During spectacles, the public took their seats according to a strict social hierarchy. Tickets indicated assigned seating, and designated pathways led spectators to their respective tiers of seats (cavea).

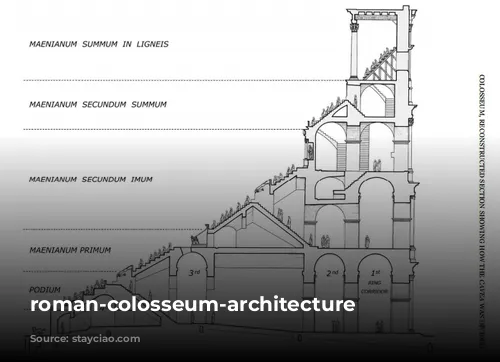

The cavea, capable of holding between 40,000 and 70,000 spectators, was divided into five horizontal sectors (maeniana), separated by corridors. The senators occupied the section closest to the arena (podium), while the upper stands were reserved for knights and other social categories. The highest columned sector (summa cavea) was designed for the plebs and featured wooden structures.

Like many modern sports arenas, the Colosseum also boasted a form of parasol: a mobile structure made of wood and cloth (velum) positioned on the top to shield the public from the sun.

Beneath the Surface: Secrets of the Colosseum’s Cellars

Hidden beneath the arena floor, cellars served as the Colosseum’s hidden machinery, playing a vital role in the spectacles. These structures, built mainly during the reign of Domitian (AD 81-96), were restored several times over the amphitheater’s five centuries of operation.

The cellars were organized into 15 corridors, constructed of tufa blocks and bricks, running parallel to a central gallery extending east-west along the ellipse’s long axis. These subterranean spaces housed the equipment needed for the games, including weapons, cages for animals, and intricate stage machinery.

A network of goods-hoists powered by winches lifted gladiators, animals, and stage props just below the arena level, accessible through trap-doors and inclined planes. The larger goods-lifts along the side corridors were equipped with cages for hoisting animals, while those in the middle cellars were used for humans and scenography. Remnants of these hoists and the load-bearing poles supporting the arena are still visible on the cellars’ floor.

The central corridor under the arena extended beneath the eastern entrance, connecting the cellars to the Ludus Magnus, the most important gladiators’ barracks, partially visible in the archaeological area between Via Labicana and Via di San Giovanni in Laterano. Another underground corridor, known as the Passageway of Commodus, connected the cellars to the outside, and the gate leading from this passageway to the cavea can still be seen near the terrace on the southern side.

A Continuing Legacy

The Colosseum stands as a magnificent testament to Roman power and ingenuity. It’s a reminder that even in the face of time, the spirit of the past can still inspire awe and wonder. While the amphitheater may have fallen silent, its stories continue to echo throughout history, beckoning us to explore its secrets and appreciate the extraordinary feats of engineering that brought this grand monument to life.