The gladiator—a symbol of ancient Rome’s brutal entertainment—was much more than a mere fighter. These professional combatants had their roots in Etruscan funeral rituals, where they were believed to serve the deceased in the afterlife. These bloody spectacles, initially intended for the dead, evolved into wildly popular public events in Rome.

From Humble Beginnings to Grand Spectacles

What began as a simple display of three pairs of gladiators in 264 BCE, at the funeral of Brutus, grew into colossal events under Julius Caesar, boasting 300 pairs of fighters. The spectacle, once a single-day affair, stretched to a hundred days under Emperor Titus, and Emperor Trajan’s triumph in 107 CE saw a mind-boggling 5,000 pairs of gladiators battling in the arena. These brutal exhibitions were not confined to Rome, with amphitheatres across the Roman Empire hosting similar gladiatorial displays.

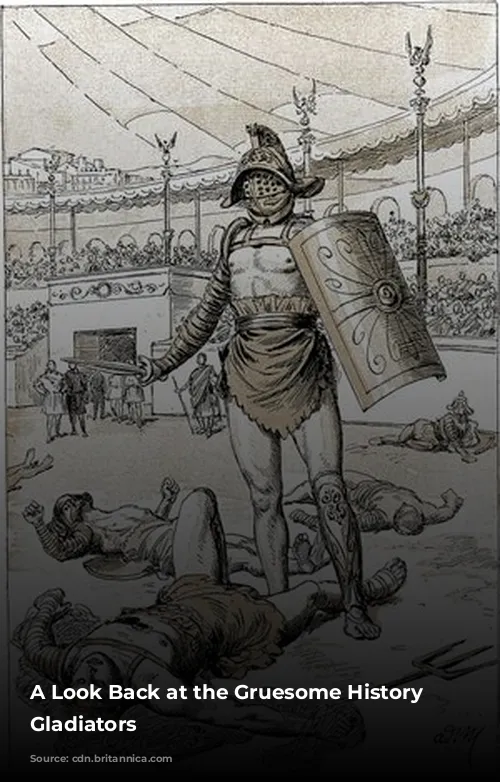

A Cast of Characters: Gladiators of Every Stripe

The gladiatorial world was diverse, with fighters categorized by their weapons and fighting styles. The Samnites, for instance, wielded the traditional weaponry of their people, while the Thracians fought with a distinctive curved dagger. The Mirmillones, named for the fish crest on their helmets, were clad in Gallic attire, battling the Retiarius, a lightly armed net-wielding fighter. Other gladiators, such as the blindfolded Andabatae, the double-sword-wielding Dimachaeri, and the chariot-fighting Essedarii, added to the variety of gladiatorial combat.

A Gory Spectacle: The Ritual of Combat

Gladiatorial contests were meticulously planned and advertised, with posters detailing the gladiators’ names, the date of the event, and the types of battles to be fought. The spectacle began with a procession of fighters into the arena, followed by a mock battle to whet the crowd’s appetite. The true battle commenced with the sound of the trumpet, with fear-stricken gladiators urged into the arena with whips and hot irons.

The crowd roared with excitement as the gladiators clashed. A wounded fighter was met with the cry “Habet!” (“He is wounded!”), and those at the mercy of their opponent would beg for mercy, raising their index finger. The fate of the defeated gladiator rested in the hands of the audience, who wielded their handkerchiefs to express clemency or turned their thumbs down for death. Victory brought rewards of palm branches and sometimes money, but the ultimate prize was survival, as gladiators who endured multiple battles could be discharged from service.

A Power Shift: The Rise of the Gladiators

Gladiators, often slaves and criminals, were subject to strict discipline, but success brought fame and even societal acceptance. Some even enjoyed the company of wealthy women. The turbulent world of politics was not immune to the influence of these fighters, as influential figures often employed them as bodyguards, leading to deadly confrontations. The most dangerous threat came from gladiators acting independently, as seen in the infamous rebellion led by Spartacus in 73–71 BCE.

A Morbid Business: The Rise and Fall of Gladiatorial Shows

The gladiator business was a lucrative venture, with individuals owning and hiring out fighters. The heads of gladiator schools, though considered a disgraceful profession, wielded significant power. The rise of Christianity, however, led to the gradual decline of gladiatorial shows. Emperor Constantine I outlawed them in 325 CE, although the practice continued for several decades. The final blow came with Emperor Honorius’s abolition of gladiatorial games in 393–423 CE, though they may have persisted for a century longer.

The gladiatorial games, with their brutality and spectacle, reflected the values of a bygone era. The gladiators, though often slaves and criminals, were also figures of immense power, capable of changing the course of history. While the bloodthirsty gladiatorial shows are long gone, they continue to fascinate and terrify us, a testament to the enduring appeal of both violence and spectacle.