The Colosseum, a towering symbol of Roman might, stands as a testament to their architectural prowess. This colossal amphitheater, the largest in the world, has weathered centuries of fires, earthquakes, and neglect, yet remains an enduring marvel.

A Project of the Flavian Dynasty

Built between 70 and 80 AD under the Flavian Emperors Vespasian, Titus, and Domitian, the Colosseum originally bore the name Amphitheatrum Flavium, reflecting its origin. Vespasian, seeking to appease a restless citizenry after the tumultuous reign of Nero, commissioned this monumental project as a gesture of populism. Construction commenced in 72 AD on the site of Nero’s lavish Domus Aurea, a symbol of his extravagance.

A Monument Built by Captives

The Colosseum’s construction was largely fueled by the labor of Jewish slaves, captured during the First Jewish-Roman War. This vast structure, an oval measuring nearly twice the length and 1.5 times the width of a modern football field, was a monumental task requiring immense human effort.

A Symphony of Stone and Iron

The Colosseum was a masterpiece of engineering, constructed from 100,000 cubic meters of travertine stone – a type of limestone quarried near modern-day Tivoli – along with Roman cement, bricks, and tuff blocks. The immense weight of this stone was held together by 300 tons of iron clamps. These clamps were later scavenged, leaving tell-tale pockmarks on the Colosseum’s walls, a silent testament to the passage of time.

A Gleaming Icon of Roman Grandeur

The Colosseum, upon its completion, was the most complex man-made structure in the world. The gleaming white travertine, rising almost 50 meters high, dwarfed the single-story buildings of the time. Its imposing scale and architectural brilliance would have inspired awe in the ancient Roman viewer, much like gazing at the Empire State Building today.

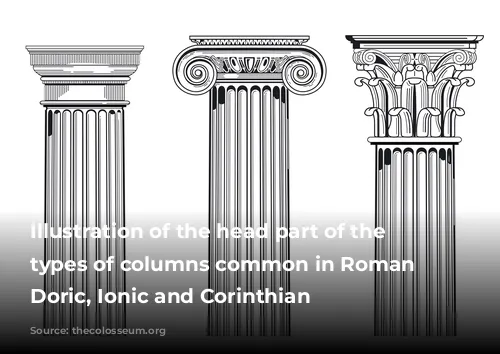

A Celebration of Architectural Orders

The Colosseum embraced the three major architectural orders of its time: the Tuscan order adorned the ground floor, evoking a sense of austerity reminiscent of the Greek Doric style. The second floor boasted the slightly more elaborate Ionic columns, while the third floor showcased the intricate and ornate Corinthian order. This progression from bottom to top reflected a gradual increase in stylistic complexity, culminating in the ornate Corinthian style at the top.

A Symphony of Arches and Columns

The Colosseum’s exterior was a harmonious blend of arches and columns, with 80 arches spanning the first three floors. These arches were largest on the ground floor, gradually decreasing in height on the upper floors. However, the fourth floor broke from this pattern, featuring flat panels decorated with carvings and insets of azurite and bronze.

Two Gates to a World of Spectacle

The Colosseum had two main entrances: the Porta Triumphalis, the gate used for triumphant processions and the entry point for gladiators, and the Porta Libitinaria, named after the Roman goddess of funerals, Libitina. This gate served the solemn purpose of removing the bodies of those who met their demise in the arena.

The Arena: A Stage for Life and Death

The Colosseum’s most defining feature was the arena, a rectangular space where gladiators, prisoners, and wild animals engaged in fierce combat. Measuring 83 meters in length and 48 meters in width, the arena floor was crafted from wood panels covered with sand from the nearby Monte Mario hill. The arena floor was equipped with trap doors to introduce and remove scenery and special effects, adding to the spectacle of the games. A 10-foot wall surrounding the arena marked the transition to the first level of seats.

A Stage Set for Drama

The arena’s walls were constructed from red and black stone blocks, contrasting sharply with the white travertine of the Colosseum, a symbolic representation of the life and death drama that unfolded on its floor.

A Hierarchy of Spectators

Surrounding the arena were the terraces, or bleachers, known as the cavea, which was divided into three tiers reflecting the social hierarchy of Roman society. The podium, closest to the arena, was reserved for the elite, including senators and high-ranking officials. As the seating ascended, the social standing of the spectators declined, with the top tier, the porticus, occupied by less affluent but still Roman citizens.

Seated in Stone and Comfort

Each seat, crafted from travertine stone, offered a width of approximately 40 centimeters. Wealthier attendees would bring cushions for added comfort. The Colosseum’s seating capacity is estimated to have been around 80,000 spectators, filling the vast space with the energy of the crowds.

Accessing the Spectacle

The cavea was also divided horizontally by access points for the public, including scalaria (stairs) leading to the stands and vomitoria, passageways leading to the exterior. The vomitoria, contrary to popular belief, were not spaces for vomiting, but rather channels for the swift entry and exit of spectators, creating a flow of people like a “spewing forth” from a location.

The Hidden World Beneath the Arena

The Colosseum’s most important feature, though hidden from view, was the hypogeum, a network of tunnels and chambers extending two levels beneath the arena. Here, gladiators and animals were kept before their grand entrances above. Added after the Colosseum’s inauguration in 80 AD by Emperor Domitian, the hypogeum connected to the arena through 80 vertical shafts. These shafts were equipped with hegmata, large moving platforms, used to transport massive beasts, such as elephants, up and down. The hypogeum was also connected to the gladiators’ barracks and nearby stables via a system of underground tunnels, ensuring the smooth flow of performers and animals. The Emperor enjoyed a private access tunnel, allowing him to enter and exit the Colosseum discreetly, avoiding the throngs of spectators.

A Monument to Roman Spectacle

The Colosseum, more than just a structure, was a symbol of Roman power, a stage for gladiatorial combat, animal hunts, and public spectacles. Its enduring legacy reflects the grandeur and engineering mastery of the Roman Empire, a testament to a civilization that thrived on spectacle and celebrated its might.