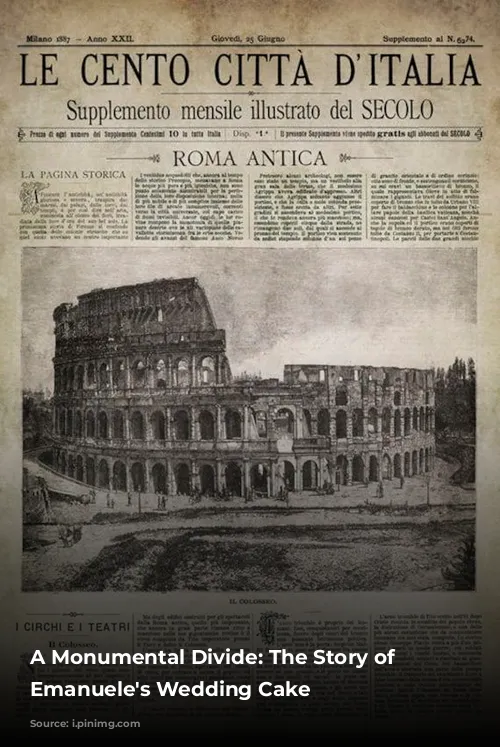

The inauguration of the monument to Vittorio Emanuele in 1911, in the heart of Rome’s Piazza Venezia, sparked a wave of controversy. Locals, with a touch of disdain, dubbed it the “wedding cake” or the “dentures,” poking fun at its over-the-top design. The massive marble structure, conceived in 1885 by Giuseppe Sacconi and completed in 1927 under the leadership of Benito Mussolini, was a source of contention not only for its artistic merit but also for the message it embodied.

This grand altar dedicated to the unification of Italy, rather than fostering unity, seemed to divide the Romans and Italians. Its imposing presence completely obstructed the view of the Roman Forum, a historical gem. This monument, meant to be a symbol of national pride, served more as a physical and symbolic barrier, casting a long shadow over the past.

A Nation Divided: The Troubled Legacy of the Risorgimento

To truly understand the conflicting opinions surrounding the monument, we must delve into the tumultuous history of Italy’s unification in the 19th century. The phrase “fare un quarantotto” – “to make 48” – aptly describes the chaotic political landscape of the time. Italy, fragmented and divided, resembled a patchwork quilt.

The Bourbons held sway in the south, the Church State dominated the center, and a collection of principalities and duchies controlled the north. Meanwhile, Austria occupied Venice under the iron grip of Marshal Radetzky. Unity was a distant dream.

Only the royal house of Piedmont-Savoy, situated in the northwest of the peninsula, championed the idea of a united Italy. With the support of Napoleon and the French, they dared to dream of a unified nation.

The Rise of Piedmont-Savoy and the Rise of Verdi

In 1849, Vittorio Emanuele, a young and ambitious leader, ascended to the throne, succeeding his father Carlo Alberto. This change ignited a wave of hope among liberals, democrats, and social revolutionaries who flocked to Turin, the capital of Piedmont, seeking a new beacon of progress.

Piedmont, experiencing economic growth, embraced the values of the 1848 revolutions: freedom of thought, speech, and political expression. This newfound energy fueled a cultural renaissance, though not without its limitations.

While Italy remained largely culturally stagnant, one shining star emerged: Giuseppe Verdi. His name became synonymous with the Risorgimento, the movement for Italian unification. His music, infused with social commentary and romanticism, captivated the hearts of Italians. The chorus of prisoners in Nabucco resonated deeply with the public, stirring their emotions and fueling their desire for liberation.

From Opera to Politics: The Symbolic Connection of Verdi and the Monarchy

The connection between Verdi and the monarchy transcended the realm of music, becoming a powerful symbol. During performances, audiences would often raise a toast to the master, savoring the “coppa Bellini”, a popular cocktail.

It was then that someone noticed that Verdi’s surname was an acronym for “Vittorio Emanuele Re D’Italia”, a powerful slogan for unity. The bond between the musician and the monarchy was forged, lasting throughout the tumultuous journey to unification.

Garibaldi’s Charge: A Warrior and a Patriot

A series of monumental events, often described as “miracles,” paved the way for the long-awaited unity of Italy. Garibaldi’s legendary march of 1000 men, from Marseille to Naples, united the south with Piedmont. Anita Garibaldi, the general’s wife, played a vital role in the Risorgimento, wielding a pistol and fighting alongside her husband.

Meanwhile, in Turin, Vittorio Emanuele’s Prime Minister, Camillo Benso, Count of Cavour, skillfully navigated international politics. In 1865, Florence replaced Turin as the capital of Italy, and a year later, Venice returned to Italian control.

The Fall of Rome and the Rise of the King

On September 20, 1870, Rome, unwillingly, surrendered to the forces of unification. Pope Pius IX, the spiritual leader of the Catholic Church, retreated to the Vatican. The Quirinale Palace, the summer residence of the Pope, now stood empty.

On December 31, 1870, Vittorio Emanuele entered the Quirinale, proclaiming Rome as the capital of Italy on the night of San Silvestro. To preserve his lineage, he retained his title, becoming known as King Vittorio Emanuele II, the first King of a unified Italy.

The Legacy of Unification: A Mixed Bag of Progress and Disillusionment

The unification of Italy brought about a vibrant cultural renaissance in Rome. Grand galas and literary readings filled the evenings, showcasing the city’s renewed energy and spirit. However, this newfound unity was accompanied by a growing sense of disillusionment.

Vittorio Emanuele, in his pursuit of power, significantly increased national debt with military spending. Parliament, representing only 2% of the population, became increasingly dominated by a sense of inconclusiveness.

The Unheard Voices: The Struggle for Representation

Voting rights remained tightly restricted based on census, excluding illiterates in both the north and the south. Almost four-fifths of Italians were denied their voice in parliament due to their inability to read. Women were also denied the right to vote.

The Risorgimento, a movement that promised equality and freedom, seemed to have left many behind. Garibaldi and other democrats, deeply disappointed by the political reality, retreated from public life.

A Marble Symbol of Progress: The Monument as a Reflection of Italy’s Literacy Struggle

Against this backdrop, the monument to Vittorio Emanuele, with its imposing size and intricate design, stands as a stark reminder of the complex legacy of unification. Its nickname, the “typewriter” (macchina da scrivere), alludes to the literacy struggle that plagued early modern Italy.

In 1878, compulsory free schooling for children between the ages of six and nine was introduced, representing a significant step towards addressing this challenge. However, the journey towards universal literacy was far from complete.

The Unfulfilled Promise: The Monument as a Reminder of Social Inequalities

The year 1848, marking the death of Vittorio Emanuele, also witnessed a mass exodus of impoverished peasants from the countryside to the capital, seeking better living conditions. Others sought refuge in countries like the United States, Argentina, and Australia, drawn by the allure of a brighter future.

The monument to Vittorio Emanuele, a symbol of national unity, ultimately reflected the deep social inequalities that persisted even after unification. It stands as a reminder that the journey to true equality and progress is a complex and ongoing one.