Imagine being the party planner for ancient Rome’s most extravagant spectacle. You’ve been tasked with orchestrating a naumachia, a simulated naval battle, and the pressure is immense! You must navigate a dizzying array of logistical challenges to create a spectacle worthy of the emperor’s gaze.

Planning a Naumachia: A Logistical Nightmare

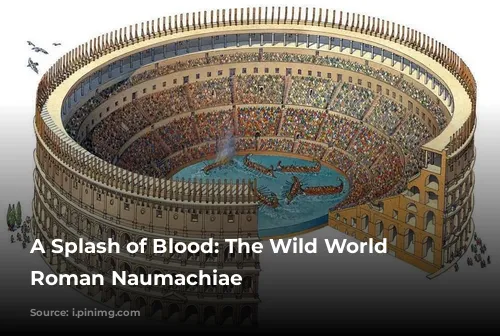

Let’s dive into the daunting details of organizing a naumachia. First, you need to find a suitable venue, which could be a lake, an arena, or even an artificially constructed basin. This space must be large enough to accommodate the warships, and you’ll need to figure out how to flood and drain it efficiently. Then, you need to recruit hundreds of oarsmen, prisoners of war, and condemned criminals to fill the ships. You’ll need a supply of weapons, boats (ranging from biremes to quinqueremes), and imported marine life for added spectacle. You must also manage the throngs of spectators, ensure security, and above all, keep the emperor happy!

More Than Just a Show: The Naumachia as a Symbol of Power

Naumachiae weren’t simply a form of entertainment. They were powerful demonstrations of the emperor’s wealth, authority, and control. These massive events required incredible resources and manpower, showcasing the emperor’s ability to mobilize the empire for his whims. Think of it as a gladiator battle on water, with fleets of oarsmen clashing in a dramatic display of naval warfare.

A History of Blood and Spectacle: The Most Famous Naumachiae

The earliest recorded naumachia took place in 46 BC to celebrate Julius Caesar’s military triumphs. It was a truly extravagant affair, featuring music, horse racing, infantry and cavalry combat, and even elephant battles. The naumachia itself involved 4,000 oarsmen and 2,000 fighting men, representing the fleets of Tyre and Egypt.

Augustus continued the tradition in 2 BC, organizing a naumachia with ships representing Persian and Athenian fleets. Later, Claudius threw his own naumachia, demanding 19,000 soldiers and 100 ships. However, the prisoners refused to fight, forcing Claudius to send in his imperial guard to incite some bloodshed.

Nero took things a step further in 57 AD, holding a naumachia in a wooden amphitheater filled with water and imported marine life, including seals and hippos. Titus, in AD 80, hosted a naumachia involving 3,000 men as part of a multi-day extravaganza.

The Colosseum: A Stage for Naumachia?

The Colosseum itself may have played host to a naumachia in 86 AD. Cassius Dio describes a violent rainstorm during a sea fight, leading to the deaths of both combatants and spectators. The underground chambers beneath the Colosseum support this possibility, but it’s difficult to imagine how they could have pumped enough water to fill the arena.

Beyond the Battles: The Naumachia as a Social Event

While the naumachia was a spectacle of blood and power, it also served as a social event. The crowds were drunken and boisterous, with prostitutes and brothels adding to the atmosphere. The chaos and anonymity of the event fueled amorous encounters, making the naumachia a hotbed of debauchery.

The naumachiae were a testament to the excesses of ancient Rome, a combination of political power, violent entertainment, and social spectacle. They were a reminder of the emperor’s might, the brutality of the time, and the insatiable appetite for entertainment of the Roman people.