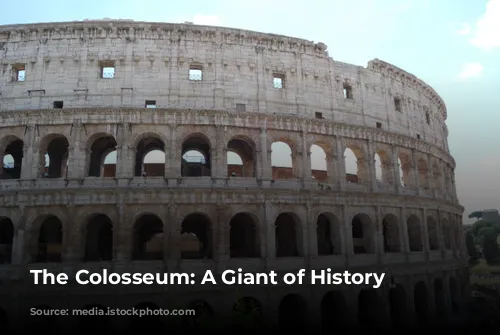

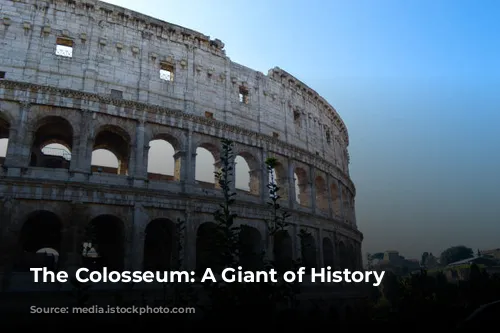

The Colosseum, also known as the Flavian Amphitheatre, is a monumental testament to Roman ingenuity and grandeur. It stands as the largest and most impressive amphitheatre in the Roman world, making it a landmark that draws visitors from across the globe. Construction began under Emperor Vespasian of the Flavia family and was completed by his son Titus, who inaugurated the arena in 80 AD.

The opening ceremony was a spectacular spectacle that spanned one hundred days. Romans were treated to a dazzling array of gladiatorial combats, wild animal hunts, and elaborate theatrical performances, a testament to the opulence of the Roman Empire. The arena itself was even transformed into a vast pool for naumachiae, reenactments of famous naval battles, a testament to the Romans’ passion for entertainment on a grand scale.

The Name of a Legend

But why is this colossal structure so widely known as the Colosseum?

The name first appeared in a prophecy by the Venerable Bede, a medieval monk. Bede’s prophecy foretold that “Rome will exist as long as the Colosseum does; when the Colosseum falls so will Rome; when Rome falls so will the world”. The name may have originated from the colossal statue of Emperor Nero, known as “the Colossus,” which once stood beside the amphitheatre. This massive statue, standing 35 meters tall, has since been lost to time.

A Triumph of Roman Engineering

The Roman Colosseum is a masterpiece of Roman architecture. Its elliptical design, created to accommodate a vast audience, and its four tiers, each with eighty arches, are a testament to Roman engineering prowess. The second and third tiers were adorned with magnificent statues, enhancing the Colosseum’s already impressive visual impact.

It is remarkable to consider that this monumental structure was built in less than a decade. How did the Romans achieve such a feat? The answer lies in their mastery of the arch, a crucial element of Roman architecture. Arches allowed the Romans to distribute the weight of heavy structures effectively, making it possible to construct massive buildings like aqueducts and amphitheatres.

A Monument Through the Ages

The Colosseum we see today is a mere skeleton of its former glory. Three-fifths of its outer wall have been lost to time. During the Middle Ages, the Colosseum was stripped of its valuable materials – marble, lead, and iron – and used to build other structures, including the Barberini Palace, Piazza Venezia, and even St. Peter’s Basilica.

The holes visible in many of the Colosseum’s columns are the remnants of this plundering.

A Stage for Spectacle and Social Hierarchy

The Colosseum could accommodate up to seventy thousand spectators, with seating arranged according to social status. The highest tiers were reserved for commoners, while the closer you sat to the arena, the higher your social standing. Senators, vestals, priests, and the emperor occupied the prime seats.

This colossal arena was a place of entertainment and spectacle, and the Romans were no strangers to sophisticated engineering solutions. The Colosseum boasted an elaborate Velarium, a massive linen tarpaulin that provided shade for spectators. This awning, operated by a hundred sailors from the Imperial fleet, was a testament to the Roman ingenuity and their love of grand displays.

The World of Gladiators and Beasts

Stepping into the Colosseum, one is immediately struck by the arena itself. While the floor, once made of brick and wood, has vanished, the cellars below reveal the machinery used to create the spectacles that captivated the Romans.

These underground levels housed lifts and hoists, their rails still visible today. They were used to raise animals and gladiators into the arena, their sudden appearances a source of surprise and excitement for the audience. This intricate system also enabled the raising and lowering of elaborate backdrops, adding to the spectacle of hunts and theatrical events.

Beyond the Blood and Gore

The shows staged in the Colosseum were a blend of symbol and spectacle, forging a connection between the people and their ruler. They provided a sense of shared experience, uniting citizens in a common passion for entertainment while offering a welcome distraction from the often challenging realities of life in the Roman Empire.

The Shows: A Variety of Spectacles

The Colosseum witnessed a diverse array of shows, each with its own time and place. In the morning, “Venationes” – hunts featuring exotic animals or battles between men and animals – were the main attraction. In some cases, these hunts served as a form of public execution, with condemned individuals left to the mercy of ferocious beasts.

The “Silvae,” staged in the arena, were a spectacle of their own. Painterly landscapes recreated the atmosphere of a forest, with trees and foliage, and animals that did not necessarily have to meet a gruesome end.

The Gladiators: More Than Just Bloodlust

The gladiators were the stars of the Colosseum, their appearances eagerly anticipated by the audience. Their entry into the arena was a theatrical event, accompanied by trumpets and drums, and cheered by their adoring fans. They would pay homage to the emperor, saluting with the famous words “Ave Caesar, morituri te salutant” (“Hail Caesar, those who are about to die salute you”).

The term “gladiator” comes from “gladius,” the short sword used by Roman legionaries. While many gladiators were prisoners of war, they often had the choice between slavery and fighting in the arena, with the prospect of freedom after a set period of time. Some were drawn to the arena by the promise of fame and fortune, seeking to escape poverty. The profession often brought them considerable wealth and even celebrity status, especially among women.

There were twelve types of gladiators, each armed differently and employing unique fighting styles. They clashed in thrilling bouts, the outcome decided by the audience. If a gladiator was wounded, he could plead for mercy, and the emperor, sitting on his stage, would decide his fate: thumbs up meant life, thumbs down meant death.

Victorious gladiators were showered with awards and money. Roman spectators, with their taste for the macabre, were enthralled by these spectacles, much like modern audiences enjoy “splatter” movies. The reality of these events, however, was far more brutal, with the stench of blood and burning flesh mingling with the scents of incense and perfume.

From Glory to Ruin and Redemption

After the decline of the Roman Empire in the sixth century, the Colosseum fell into disrepair. Its walls became home to hermits, hospitals, and even a cemetery. In the Middle Ages, it was looted for its materials, stripping it of much of its splendor.

However, the Colosseum was eventually saved from destruction. Pope Sixtus V planned to demolish the Colosseum for building materials, but Pope Benedict XIV declared it a sacred monument dedicated to the Passion of Christ, placing a cross on a pedestal in its center. This act of dedication transformed the Colosseum into a symbol of Christian martyrdom.

Today, the Colosseum stands as a reminder of the enduring power of ancient Rome. For tourists, it offers a glimpse into the grandeur of the past, echoing the words of Charles Dickens: “seeing the ghost of old Rome floating over the places its people walk in.”