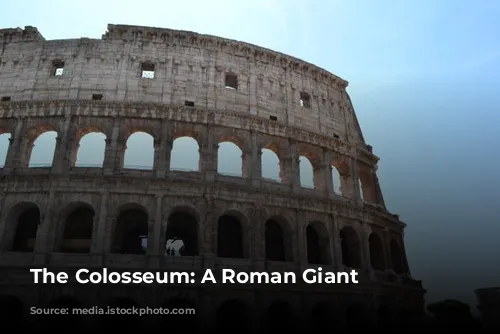

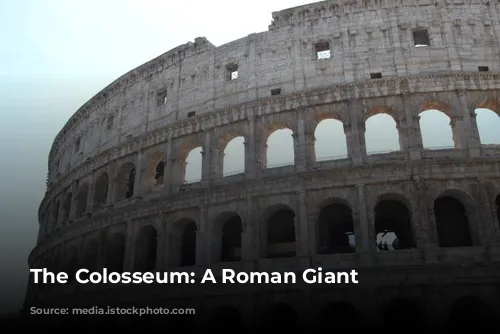

The Colosseum, known in ancient times as the Flavian Amphitheatre, stands as a testament to the grandeur of the Roman Empire. This imposing structure, the largest amphitheatre ever built in the Roman world, is not only a symbol of Rome’s power but also one of the most recognizable landmarks in the world.

A Monumental Beginning

Construction of the Colosseum began under Emperor Vespasian of the Flavian dynasty and was completed by his son, Titus, in 80 A.D. The inauguration, a 100-day spectacle, was an extravagant display of Roman might. Thousands of animals were slaughtered, and naumachiae, elaborate naval battles staged in the arena flooded with water, thrilled the crowds. The sheer scale of these opening ceremonies, described by the historian Suetonius as featuring 5,000 animals, provides a glimpse into the opulence of Roman entertainment.

The Name’s Origins

The name “Colosseum” didn’t appear until centuries later. It is believed to have originated from the Colossus of Nero, a massive statue of the emperor that once stood nearby. The Venerable Bede, a medieval monk, is credited with first mentioning the Colosseum in his prophecy: “Rome will exist as long as the Colosseum does; when the Colosseum falls so will Rome; when Rome falls so will the world”.

An Architectural Marvel

The Colosseum is an impressive example of Roman engineering. It’s elliptical shape, designed to accommodate a larger audience, is constructed from travertine stone, giving it a stunning white facade. The building, boasting four levels, is a masterpiece of Roman architecture.

The Construction Mystery

The Colosseum’s construction was a monumental feat, completed in less than a decade. The secret lies in the Romans’ mastery of the arch. This innovative architectural technique allowed them to distribute weight effectively, enabling the construction of massive structures like the Colosseum and the famous Roman aqueducts.

From Arena to Quarry

The Colosseum, now a mere skeleton of its former glory, has endured centuries of neglect and repurposing. During the Middle Ages, its valuable materials were plundered, with marble, lead, and iron being used to construct buildings like the Barberini Palace and St. Peter’s Basilica. The holes visible in the Colosseum’s columns are a testament to this historical exploitation.

A Seat for All

The Colosseum could hold up to 70,000 spectators, each with a view of the arena. Seating was strategically arranged according to social status, mirroring the hierarchical structure of Roman society. The upper tiers were reserved for the common people, with separate sections for men and women. As you descended towards the arena, the social status of the occupants increased, with senators, vestals, priests, and the emperor occupying the front row seats.

Sun Protection and Spectacles

Like modern sports stadiums, the Colosseum featured a velarium, a large linen canopy, to shield spectators from the sun. This ingenious system, controlled by 100 sailors from the Imperial fleet, provided shade for the entire arena.

The arena itself was a stage for a wide variety of spectacles, from gladiator battles and wild animal hunts to staged battles and even theatrical performances. The Colosseum’s underground chambers, equipped with lifts and hoists, housed the machinery that brought these spectacles to life. Animals and gladiators would appear through trapdoors in dramatic fashion, creating surprise and awe in the audience.

The Gladiators: Heroes and Martyrs

Gladiators, whose name derives from the “gladius” (short sword) used by Roman legionaries, were not always prisoners of war forced to fight. Many were volunteers, motivated by the promise of freedom, wealth, and fame. They trained in gladiatorial schools like the Ludus Magnus, preparing for their battles in the Colosseum.

Gladiator fights were a highlight of the Colosseum shows. The gladiators, often greeted as heroes by their fans, would enter the arena from underground tunnels, parading before the emperor and the crowd. Their battles were often a life-or-death struggle, with the outcome determined by the emperor’s decision, signaled by a thumbs up (life) or a thumbs down (death).

Beyond the Brutal Spectacle

The Colosseum’s shows were not just violent entertainment; they served as a way to unite Roman citizens and their leader. These public events offered distraction from political problems while showcasing Roman power and cultural influence.

The Colosseum Today: A Timeless Symbol

The Colosseum, despite its long history of decay and repurposing, has risen again as a symbol of Roman grandeur. It is a reminder of a time when empire and spectacle were intertwined, and the Colosseum was the ultimate stage for the grandest of shows. Today, visitors from around the world continue to flock to this ancient marvel, captivated by its history and the echoes of its past.