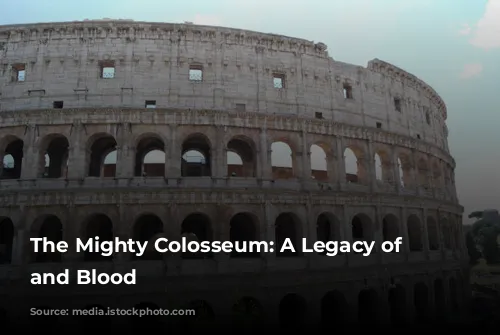

The Colosseum, known also as the Flavian Amphitheatre, stands as a testament to the grandeur of the Roman Empire. Its sheer size and imposing presence make it the largest and most awe-inspiring amphitheatre in the Roman world. Emperor Vespasian, from the Flavia family, initiated its construction, and his son, Titus, proudly inaugurated it in 80 AD.

The opening ceremony was a spectacle of unimaginable extravagance, lasting a staggering one hundred days. The Roman public witnessed breathtaking feats of skill and bravery, with gladiatorial combats, animal hunts, and elaborate displays of power. The sheer scale of the events was mind-boggling, with an estimated 5,000 animals meeting their demise.

The Colosseum was not simply a stage for brutality, however. It was a place where the people of Rome could gather to witness the strength and prowess of their gladiators. The arena was often transformed into a vast body of water, hosting grand naumachias – elaborate reenactments of ancient naval battles.

The Colossus and the Birth of a Legend

The name “Colosseum” emerged from a medieval prophecy by the Venerable Bede. He predicted, “Rome will exist as long as the Colosseum does; when the Colosseum falls so will Rome; when Rome falls so will the world”. The origin of this name is believed to be the Colossus of Nero, a massive statue of the emperor, towering at 35 meters, that stood near the amphitheatre.

The Colosseum, once dazzling white, was covered in exquisite travertine stone slabs. It is an elliptical structure, designed to accommodate a large number of spectators. Its four floors, with eighty arches each, were adorned with magnificent statues. This architectural masterpiece was completed in a mere ten years, a testament to Roman ingenuity.

A Symphony of Arches and Ingenuity

The Romans mastered the art of the arch, which allowed them to distribute the weight of massive structures effectively. The Colosseum exemplifies this skill, with its intricate use of arches that supported the entire structure.

One can envision the Colosseum as a series of aqueducts stacked upon one another. The colossal walls were once an awe-inspiring sight, but time has taken its toll. The ravages of time have left only a skeletal remnant of its former glory.

Plundering a Monument: A Legacy of Greed

The Colosseum fell into disuse during the Middle Ages. The magnificent marble, lead, and iron that once graced its walls were stripped away by popes, who used the salvaged materials to construct palaces, plazas, and even St. Peter’s Basilica.

Even today, we can see evidence of this plunder. Holes remain in the Colosseum’s columns, where the lead and iron nails that once bound the marble blocks were removed.

A Stage for Blood and Spectacle

The Colosseum could accommodate an astonishing 70,000 spectators. The seating was cleverly designed, with a tiered arrangement that ensured a clear view for everyone, regardless of their position.

Entry to the Colosseum was free for Roman citizens, but seating was allocated according to social status, much like modern theatres. The commoners occupied the higher tiers, while the more privileged enjoyed the lower seats, closer to the action. The front row was reserved for the elite, including senators, vestals, priests, and, of course, the emperor.

The Colosseum was equipped with a sophisticated roof system called the Velarium, offering protection from the sun. This ingenious design involved a vast linen tarpaulin stretched over the arena using ropes, winches, and wooden poles. It took a hundred sailors from the Imperial fleet to maneuver this massive structure, coordinating their movements with the beat of a drum.

The Arena: A Stage for Cruelty and Skill

Entering the Colosseum, the arena lies before us. The floor, once a mixture of brick and wood, has vanished, revealing the cellars that housed the equipment used for the games.

Two subterranean floors housed lifts and hoists with counterweights, remnants of which are visible today. These were the special effects of ancient Rome, used to elevate animals and gladiators, who would suddenly appear in the arena, surprising the audience with dramatic entrances.

A Tapestry of Entertainment

The Colosseum hosted a variety of spectacles, all carefully orchestrated and timed. The morning typically began with venationes, brutal fights between exotic animals or between men and animals.

Public executions were sometimes staged, leaving victims to the mercy of ferocious beasts. Silvae were particularly spectacular events, with elaborate sets created by skilled painters and set designers. The arena was transformed into a forest, teeming with animals that were not always killed.

There were also less gruesome events. One memorable display involved an elephant trained to write words in the sand using its trunk.

Contrary to popular belief, the Colosseum was not used for the execution of Christians.

The Gladiators: Heroes of the Arena

The highlight of the day was undoubtedly the gladiatorial combats. After a midday break, the arena was cleared of bodies, and fresh sand was spread across the floor.

The roar of the crowd reverberated through the Colosseum as gladiators emerged from a tunnel connected to the Ludus Magnus, the Gladiators’ barracks. They were welcomed as heroes, much like modern sports champions.

Gladiators, usually prisoners of war or impoverished men seeking fame and fortune, performed a brief walk around the arena before saluting the Emperor’s stage with the iconic words, “Ave Caesar, morituri te salutant” (Hail Caesar, those who are about to die salute you).

A Symphony of Swords and Strategies

There were twelve types of gladiators, each with their unique weapons and fighting styles. The Retiarius, armed with a net, a trident, and a knife, battled against heavily armored gladiators wielding shields and sickles.

The contests were carefully designed to ensure dramatic and thrilling encounters.

If a gladiator was wounded, he could appeal for mercy by raising an arm. The fate of the defeated gladiator rested in the hands of the Emperor, who would decide whether to spare him or condemn him to death. A thumbs up signified mercy, while a thumbs down signaled execution.

Victorious gladiators were rewarded with golden palm leaves and substantial sums of money. After each battle, servants, dressed like Charon, the Ferryman of the Underworld, ensured that the wounded were truly dead, ending their suffering.

A Legacy of Blood and Glory

The Roman people, much like modern-day audiences, had an insatiable appetite for violence. They reveled in the brutal spectacles, a passion comparable to today’s fascination with “splatter” cinema.

The brutality of the Colosseum was undeniable, with the stench of blood, burnt flesh, and wild animals filling the air. Incense and perfumes could not mask the raw intensity of these events.

After the decline of the Roman Empire in the 6th century, the Colosseum fell into disuse. Its walls became shelter for various groups, including confraternities, hospitals, hermits, and even a cemetery.

A Symbol of Faith and Redemption

From the Middle Ages onwards, the Colosseum has stood as a monument to Rome and the world, attracting countless visitors.

Threatened with demolition by Pope Sixtus V, it was declared a sacred monument dedicated to the Passion of Christ by Pope Benedict XIV. A cross was placed on a pedestal, symbolizing the suffering of all Christian martyrs. This cross still marks the beginning of the Stations of the Cross, a solemn procession held on Good Friday.

This act of consecration shielded the Colosseum from further destruction and led to its restoration and preservation by subsequent popes.

A Ghost of a Glorious Past

Today, visitors to the Colosseum experience a profound sense of history. The words of Charles Dickens perfectly capture this feeling, “Seeing the ghost of old Rome floating over the places its people walk in”.

The Colosseum stands as a poignant reminder of the grandeur and brutality of the Roman Empire. It is a place where history and myth intertwine, offering a glimpse into a world long gone.