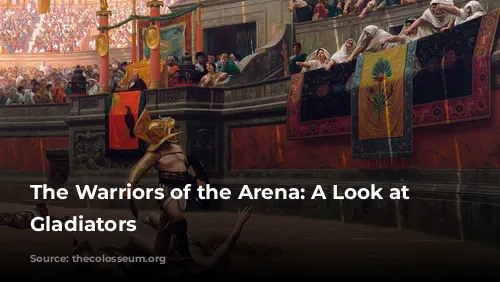

The gladiator, a name that conjures images of fierce warriors clashing in bloody combat, is perhaps the most iconic figure from ancient Rome. While popularized by films like “Gladiator” and “Spartacus”, the reality of these men is often obscured by myth.

Who were these gladiators?

Most gladiators were slaves with no rights in Roman society. Their lives were a stark contrast to the legendary victories that some achieved. While a few ascended to fame and freedom, the vast majority perished anonymously in the sand.

A Diverse World of Gladiators

The gladiatorial world was diverse, with over two dozen types of gladiators, each distinguished by their weapons, armor, and fighting style. Some of the most recognizable include:

-

The Murmillo: Heavily armored, these warriors wielded a gladius (sword) and a large, oblong shield. Their distinctive helmet featured a fish-shaped crest.

-

The Thraex: Similar to the Murmillo, but armed with a curved thracian sword and a smaller, rectangular shield. Their helmet, too, covered the entire head but bore a griffin instead of a fish.

-

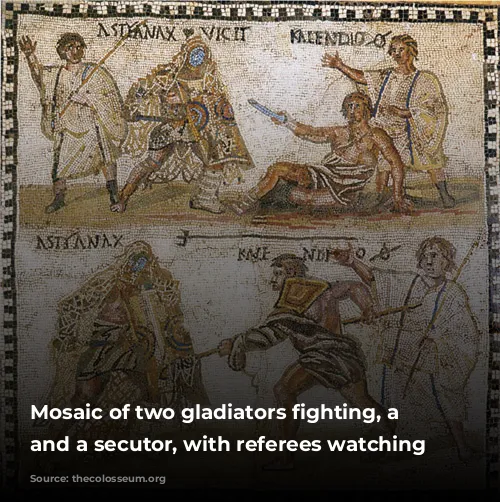

The Retiarius: These famous gladiators relied on a net and a trident, employing agility and cunning. Wearing lighter armor and lacking a shield, they aimed to ensnare their opponents before striking with their spear.

-

The Essedarius: These were mounted gladiators, who fought from chariots. Sadly, very little is known about them.

-

The Hoplomachus: Meaning “armed fighter” in Greek, these gladiators were equipped with a throwing spear, a short sword, a small, round shield, and a plumed helmet.

While women did occasionally participate in gladiatorial combat, they were considered an oddity, a peculiar form of entertainment rather than a mainstream type of gladiator.

A Life of Brutality and Discipline

Gladiators lived within the infame class, their lives forfeit to their masters. The gladiator schools were strict institutions where training was harsh. Evidence suggests that gladiators could be killed for misbehavior.

Each gladiator trained under a master specializing in their particular fighting style, and the different groups were kept separate, possibly to prevent conflicts among future arena rivals.

Upon entering a gladiatorial school, individuals (often condemned to this life as punishment for a crime) would sign a contract. This contract outlined the type of combatant they would become, their annual fight schedule, and their transfer into their master’s ownership.

From Obscurity to Fame

While most gladiators met their end in anonymity, some rose to fame and their names echo through time.

-

Crixus, a Gallic slave, escaped captivity and became a leader in the Third Servile War, a rebellion of slaves against the Roman Republic.

-

Emperor Commodus, known for his love of gladiatorial combat, entered the arena himself. However, his cruelty in pitting disabled opponents against him in staged battles made him reviled and ultimately contributed to his assassination.

-

Priscus and Verus, two gladiators who fought at the inauguration of the Flavian Amphitheater, battled for hours before agreeing to a draw. Their courage earned them freedom from their masters.

-

Spiculus, a gladiatorial rock star, was a favorite of the tyrannical Emperor Nero. Despite being called upon by the fallen emperor to end his life, Spiculus refused, leaving Nero to take his own life.

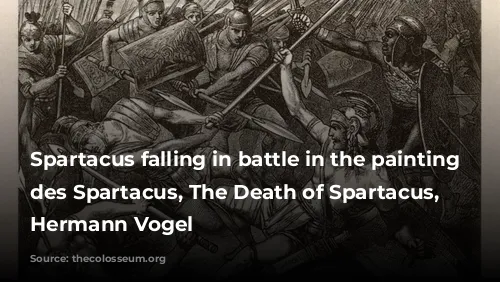

Spartacus, perhaps the most famous gladiator of all, was a real person. A Thracian soldier turned slave, he led a massive rebellion of gladiators and slaves. Although his forces were ultimately defeated in the Third Servile War, his legacy as a symbol of defiance against oppression lives on.

The Ritual of Combat

Gladiatorial combat was typically one-on-one, with opponents chosen for their complementary styles. Murmillos, for instance, often faced Thracians or Hoplomachus, while Retiarius usually fought gladiators equipped with conventional weapons.

Fights were carefully organized and overseen by referees. While death was not always the outcome, fights often concluded without a fatality. Gladiators were expensive investments, and their owners wanted them to survive as long as possible. Early Colosseum fights were more brutal, but as time passed, contests became less lethal as replacing dead gladiators proved costly.

Beyond the Arena: Other Forms of Bloodsport

While often associated with gladiators, wild beast fights were actually separate from gladiatorial combat.

Criminals and prisoners of war were condemned to damnatio ad bestias, a public execution by wild animals. There was also a specialized class of combatant, the bestiarus, who fought against beasts, but they were not considered true gladiators.

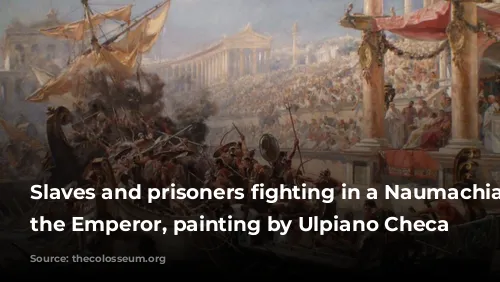

Naumachia, staged naval battles featuring real ships and combatants, were among the most spectacular Roman blood sports. These events, unlike the regular gladiatorial contests, were reserved for special occasions, such as Julius Caesar’s triumph. Participants were often prisoners of war or condemned criminals, and the battles were more brutal and deadly than gladiatorial combat.

Naumachia were usually held in specially constructed arenas, large channels or artificial lakes. The Colosseum itself hosted two naumachia shortly after its inauguration.

The legacy of Roman gladiators continues to captivate us. These warriors, though often forgotten, played a significant role in Roman society, their lives a mixture of brutality, discipline, and, for a select few, fleeting fame. Their stories serve as a reminder of the complex and often violent nature of the Roman world.